Breadth vs. Depth: Assessing Prior Founder Experiences

How early stage founder experiential breadth can drive deep investor returns through idea signaling, effective leadership, flexible thinking and professional learning

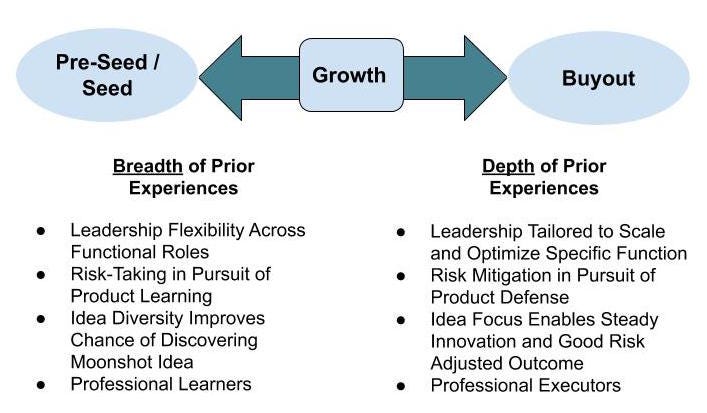

Welcome back to The Innovation Armory. This week’s piece focuses on the relative importance of breadth vs. depth of professional, intellectual and personal experiences when assessing founders across company stages. I argue that the younger the business, the more investors ought to seek out founders with diversity and breadth of experiences across industry domains.

Separately, our world is experiencing a significant rise in nationalism, with technology being politicized and at the forefront of many of these conversations. For example, India’s decision to ban TikTok and threats by the Trump administration to do the same in the United States. Next week’s piece will examine the effects of nationalism and shifts in the post World War 2 liberal world order on entrepreneurial innovation and technology investing strategies.

When looking to back new founders, investors often look towards subject matter experts who are specialized in a domain relevant to their thesis. This makes sense at a surface level. Investors (especially sector generalists) want confidence that their founders are smarter in their sectors than they are. They seek founders who are more likely to know all of the relevant trends in a sector, increasing the probability their vision is moderately attuned to sector needs, reducing potential downside of a new platform investment. These entrepreneurs have more focused functional experience to execute on a well-defined mission. However, especially with earlier-stage businesses and smaller checks, breadth and range of professional and intellectual experiences should have a higher probability of realizing an exceptional investment outcome. Breadth of domain experience should be more predictive of founder success for early stage businesses, i.e. pre-seed / seed.

The earlier the company, the more important it becomes to identify founders with experiences that highlight intellectual and professional thought diversity. What are the primary benefits of intellectual and professional range of experiences at earlier stages of company building?

Cohesive and Diverse Team Building

Founders with experience working across sectors and in different types of roles can better identify talent across functional areas. Early-stage founders with limited resources need the perspective to be able to recruit and empower leaders in sales, finance, product and other functional areas. For earlier stage investments, the existing team is smaller and departments are more integrated. Dynamic team building needs to cut across functional silos. For later-stage businesses, because the team is largely built out already and functional silos more clearly defined, leadership is tailored more to scaling out specific functional areas that are already structurally defined.

Differential Underdog Mentality

Founders with diversity of experience are armed with a diverse war chest of skills they have learned from working in different roles. However, by choosing not to specialize in a sector early, they likely has less personal brand capital in any one industry and therefore are more likely to be under-estimated by entrenched players. An underdog mentality is also a better defense against over-confidence in an initial idea, enabling greater flexibility in strategy around potential pivots. The early-stage founder toolset plus the network of an established VC is a winning combination. Being perceived as an underdog allows a startup to stay under the radar and better hyper-scale. For more mature investments, management teams need to be tried-and-true in a particular sector to fend off competition as they already have a target on their back by that stage.

Effective Culture Builders

Breadth of professional roles earlier in one’s career maximizes exposure to different types of people with separate working habits, values, cultures and personalities. Early stage founders actively build their startup culture from the ground-up and diversity of interpersonal experiences in the workplace enables them to better choose the pillars of their culture and screen for candidates who will be culture-enhancing. Whereas, management for late-stage companies are culture preservers as it becomes increasingly tougher to change culture as an organization scales. Breadth is critical for culture building and a robust and inclusive culture is important to attracting the best talent and diverse thinkers.

Patience and Grit

Those who work in many roles (assuming they spend a meaningful amount of time in each) are hard workers that are willing to defer short-term gains to gain breadth of experience. Choosing not to specialize early entails trading off lower pay and prestige in a given industry to reset and have a new experience in a totally different sector. Being forced to do this due to lack of hard work or poor performance is of course a negative quality in a founder. Choosing consciously to make these sacrifices demonstrates intellectual maturity and patience. Early-stage founders need to be patient while crystalizing their vision and nurturing a business idea. Market feedback will necessitate product changes to achieve product market fit. Once a business is sound from a product development and unit economics perspective, moderated management eagerness can become a catalyst to scale faster and disrupt markets faster than one’s competitors.

Commitment Signals Better Idea Quality

Because early-stage founders with breadth are patient, their choice to commit to one industry and idea sends a strong signal of vision quality for the new venture. It means that after thinking through the totality of their experiences across many sectors, their current venture is the best business and financial opportunity for their own livelihoods that they have identified. Founders with breadth are most likely to have considered numerous potential venture ideas and are more likely to also have considered the right time to launch a venture. They had a professional toolset flexible enough to launch many different types of ventures (or alternatively work in a well-paying corporate job) and so are more likely to have been refined and selective in choosing what business to eventually found.

Insatiable Curiosity for Tinkering

One of the main jobs of an early-stage founder is to be a professional learner. Entrepreneurs want to raise early-stage funding to iterate on products, trial offerings with customers and receive market feedback in the most capital efficient manner. Those who intentionally chose breadth of experience instead of specializing earlier are more likely to be insatiably curious and love learning. These founders are not ignorant or in-denial about what they do not know. Rather, they love the process of learning and actively seek to resolve gaps in knowledge and uncertainties to build a better business. For later stage businesses with more established product positioning, curiosity in leadership is less important than absolute existing knowledge base. Deeper industry learning experiences with moderate curiosity are better for defending a strong existing market position.

Highly Adaptable

Founders with breadth of experiences enjoy the challenge of adapting to new environments, whether that be getting smart on a new sector or adjusting to a new office or city. Startup founders need to be adaptable. Many businesses change substantially from inception as market needs change, the competitive landscape evolves and new technologies emerge. Early-stage founders with breadth can adapt faster and smarter by applying learning from prior change to tackle a new problem. While adaptability is important for later-stage businesses, management’s goal is to minimize the need to adapt by leveraging an existing competitive moat to solidify industry position.

Sector Parallelism Enhances Novelty of Approach

Working across industries provides a unique ability to connect the dots and draw interesting parallels between common challenges and solutions between sectors. Industry breadth can therefore make a founder a better problem-solver by drawing on and transforming best practices in other industries to craft a novel approach in the sector of one’s new venture. This “outsider” perspective increases the probability an early stage founder can identify a moonshot disruption opportunity by applying a novel or contrarian approach to a mature sector, yet one that has been partially validated within other industries. More mature companies tend to focus more up-market with clients who may be unwilling to try such a contrarian technological approach until it is validated by smaller businesses or early adopters.

As mentioned in the “Patience and Grit” section, it is important for investors to identify which early stage founders have purposefully tried to develop intellectual and professional range rather than individuals who were unsuccessful in an industry and forced out of roles. The former signals excellence and the latter signals mediocrity and potential management / work ethic issues.

Technology investors should be mindful of how their stage / check size strategy impacts the relative ideal weighting of founder depth vs. breadth when backing a management team. Entrepreneurs pitching to investors should be cognizant of a) their own business size and b) the venture capital firm’s investing strategy and leverage that knowledge to selectively highlight their relative breadth vs. depth strengths.

To learn more about the benefits of intellectual and professional breadth and scientific studies on its importance, I’d recommend checking out Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World by David Epstein.

All Innovation Armory publications represent expressly my individual views and the views of those interviewed and do not represent the views of companies with which I have previously been associated or with which am soon to be associated. These publications are my personal opinions and are not meant to be relied upon as a basis for investment decisions.