The Dark Side of Innovation

How Unforeseen Consequences of Technology Have Shattered Our Concept of Truth

Welcome back to the Innovation Armory. At the core of the horrifying events in the Capitol over the last few weeks is the ease with which misinformation in the modern era can be created and distributed to large portions of the global population. This piece explores the role that technological innovation has played in amplifying misinformation and how emerging technology companies and initiatives can play a role in solving this crisis of digital truth.

Information technology advances over time have created substantial economic and social benefits to society through increased connectivity. However, each information technology improvement also carries a dark side. This dark side is not necessarily predictable at the onset of a new technology’s implementation, but becomes apparent with scale. In the case of information technology, as the cost of creating, producing and disseminating content decreases with innovation, the barriers to spreading misinformation have gradually eroded. The era of AI has the potential to decimate any and all barriers that remain. The era of the internet took the cost of distributing information effectively to zero and thereby amplified the power of misinformation substantially more than other forms of media advancement throughout history.

The power of a misinformation campaigns can be understood as a function of both the believability of the misinformation and the virality / ease of its distribution. Continuous information technology improvements culminating with the rise of social media networks have aided in improving the virality of all content regardless of whether it is accurate or based in misinformation. Improvements in artificial intelligence have rendered it possible to manipulate videos and images to make it look like someone said or did something they did not. This type of manipulation is just one type of disinformation campaign and is called a deepfake. Deepfakes represent the next level of believability for misinformation campaigns. The below shows an original and “Deepfaked” version of a popular Alec Baldwin SNL impersonation of Donald Trump. In the clip to the right, an organization called “Derpfakes” inserted President Trump’s face on top of baldwin’s face frame-by-frame making it appear as if Trump was actually reciting Baldwin’s satirical impersonation. This video was actually banned in the US due to its high believability and virality, but the technology exists to replicate these campaigns for other leaders, businesses and situations:

While deepfakes are merely one vector of attack for misinformation campaigns, I believe they represent an inflexion point in our eroding perception of truth online by helping align content believability with the low cost viral distribution of social media at a time when the US regulatory paradigm has yet to shift to properly regulate the businesses and entities that contribute to the misinformation ecosystem. I caught up with Nina Schick to hear her perspectives on our corroding online information ecosystems. Nina is an expert on deepfake and misinformation technologies who has advised a group of global leaders including president-elect Joe Biden and Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the former Secretary General of NATO, on deepfakes. If you enjoy the interview below, you should check out her recent book Deefakes: The Coming Infocalypse.

My Interview with Nina Schick (Author and Consultant on Misinformation Campaigns and Deepfakes)

SN: What are the key ways that technological innovation has backfired in terms of its impact on the innovation ecosystem? What has been the dark side of innovation?

NS: When you talk about disinformation, it is as old as society itself. Technology did not create misinformation. The technology has just amplified the best and worst in humanity. The problem with businesses in the innovation age is that they were conceptualized by their utopian founders as this unmitigated good for humanity, connecting and improving the world. They were not built with any safety mechanisms against the potential misuses of this technology. Over the past few years, bad information is not only easier to create, but can also go viral within seconds. We are coming into the next generation of that where all visual media can be faked with technology. The foundational premise that this technology would simply be used for good is mistaken. This is why it is my mission to raise the alarm ahead of the coming age of synthetic media. There is no doubt that the future of media is synthetic unless we build information safeguards directly into media.

SN: Could you discuss what are society’s primary vectors for defense against misinformation campaigns?

NS: The first part of the challenge is conceptualizing the threat. When you look at Russian interference to AI generated fake porn to mobs killing people in India because of viral misinformation of WhatsApp, it all makes more sense when you think about it in the context of the corroding information ecosystem apocalypse. The solution must be society-wide and a networked approach that includes governments, policymakers, tech platforms, startups targeting synthetic media. At its best, there is a need to create a global standard. That is difficult. But there are various groups pursuing smaller efforts that could grow into more impactful initiatives. The most progressive initiatives I have seen have come from industry. For example, Adobe’s content authenticity initiative where they work with True Fake and Qualcomm to solve part of the problem for the authenticity of media. You also have Project Origin, an initiative between BBC, Radio Canada and the NYTimes trying to build the technology to prove the provenance of authentic media. There is also a category of technical solutions to implement around detection and authentication. At the society level, we need to build resilience and update our legal and regulatory frameworks to adapt to this paradigm change.

SN: Besides existing methods of misinformation, there are always new businesses and technologies being created that could be extrapolated for negative use cases. How can governments get ahead of the innovation curve and work collaboratively with entrepreneurs to prevent new innovations from posing further issues?

NS: From my experience of working with policymakers, they are so far behind. They need to begin working much more closely with technologists and those innovating in new technology methods. There is not enough of a dialogue occurring between governments and technology communities. There are initiatives underway with some governments around detecting deepfakes, for example, DARPA’s investment in MediFor. We have seen over the past 5 years though, how reactive governments have been to technology.

SN: How do you think big tech did in combatting misinformation in the prior election and if heavy regulation is not the solution to moderating big tech, what is the solution?

NS: Obviously the big tech companies bear a lot of responsibility. But I think the only way we can conceive of the solution is by fixing the ecosystem itself. Ideally, you want to start building a trust layer into the internet at each interaction point, embedding the provenance technology, detection software and tracing tools to correlate identities to content published. To implement this, you need buy-in from the government and political will as well as public engagement. It is such a huge project, I don’t see it happening in the near future. With regards to their reaction in the 2020 election, big tech has actually been pretty good at showing how they can respond. The issue is that the debate around censorship is too partisan in the US. Specifically with the Hunter Biden story, it appears have been a hack and dump campaign with maybe some elements of truth. It turns out that the intel company and Martin Aspen (intel officer) were fake. This was exactly the type of scenario that social media platforms were preparing for. Because the environment is so partisan, it was seen as censorship. The big tech companies are damned if they do and if they don’t. If they don’t act to stop the spread of this information, they will be accused of aiding misinformation and if they do then they will be accused of gross censorship. This is the time we need to start to debate where the lines are between free speech and censorship and fact checking. All of this comes back to how we as a society rewrite the rules to meet this paradigm shift. The rules were built for the analogue age, not digital and now we are entering into the AI age unprepared.

SN: With regards to the trust layer you referenced, are there any specific companies you think will play a key role? How large of an issue is the way existing media businesses have been structured specifically around advertising?

NS: Many studies have illustrated that people tend to focus more when there is a bad / fake story, which drives more advertising revenue. The advertising based model definitely needs to be revisited vs. the subscription model. Separately, there are numerous businesses working to achieve a trust network vision. One is Sentinel. It will be interesting to see if they will be able to work collaboratively with the Estonian government to effectively build this trust layer into communication networks. As we go further into 2021 and 2022, there will be more companies focused on the detection space. To date, more of the private sector effort has been focused on provenance.

SN: How important do you think international collaboration is and what are the geopolitical barriers to tackling these issues?

NS: If you believe liberal democracy is the best world order, fixing information ecosystems is absolutely imperative. It should be an issue of national priority to work with liberal Western allies of importance similar to existential threats such as climate change. Having said that, I have seen how weak the international order is becoming through my prior government work. This doesn’t work unless the US buys into this system. You cannot get collaboration unless the US leads the way in the international arena. Of course, for actors like China and Russia, it is in their interests to undermine such efforts. This corroded information apocalypse is truly an existential threat to Western democracy. As the results of the election have shown, the biggest threat to the US election did not come from Russian or Chinese interference, it came from within the US from the president himself in the form of a disinformation campaign: the idea that there was vast voter fraud. Even as Trump leaves the white house, that narrative and pernicious seed is going to fester and grow. It is not only true on the republican side of the divide. The democrats could do the same thing in the next election and this cycle of disinformation in politics is actually what is the most corrosive to democracy.

Provenance and Detection -- The Golden Duo

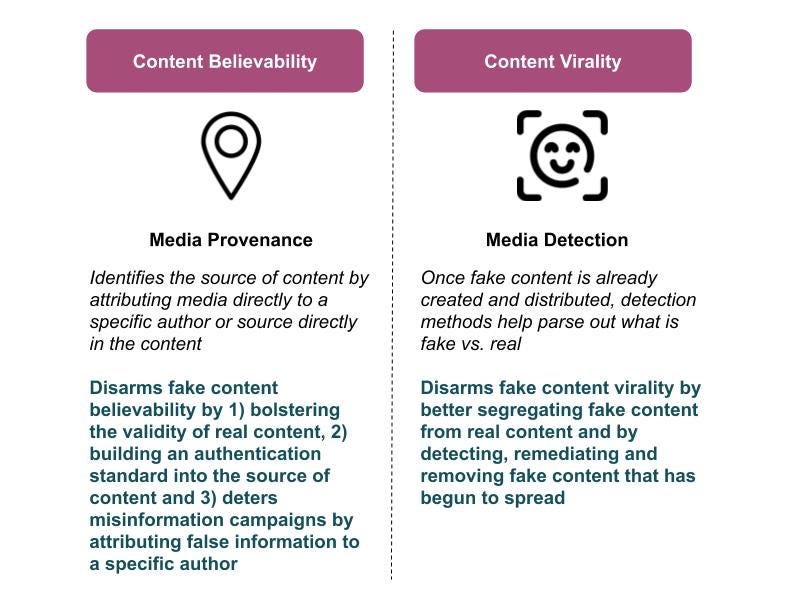

Nina’s focus on a dual-phased defense against misinformation ties well into the above framework for what drives an effective misinformation campaign: believability and virality. Provenance and detection can methods work complementarily to disarm the growth vectors for fake news and misinformation campaigns:

Companies aiming to address the media provenance issue need to solve for key steps in an effective provenance system including:

Identity Establishment - establishing the author and/or source of a piece of content in a way that is traceable over time, consistent and repeatable

Identity Ranking - creating a public domain for the authenticity and reliability of the various domains and identities that are established

Identity Alarm - if a piece of content is attributed back to an incorrect or inaccurate source, provenance systems need to have a way of signaling to detection and remediation tools that there is harmful content that ought to be targeted

It is important that the methods for authors and content creators to abide by this provenance system are broadly accessible. There is so much polarization in opinion online today that if the system is not easily understandable and convenient to utilize, then bad actors can label the lack of accessibility as a means of censorship in order to stymie efforts to block misinformation campaigns.

Similarly, for software tools that help with detection and remediation of fake content, explainability is very important. Much of the investment in detection methods to-date have leveraged AI-based or machine learning algorithms. While these algorithms can be highly effective in distinguishing between fake and real content, because their models are highly complex and self-learn, their results can sometimes be less explainable than filtering decisions made by non-AI based algorithms or by humans. If content is detected and removed due to being labelled fake and invalid, media sites need to be able to explain to their user base and the general public why it was removed or else risk that their removal will be similarly deemed censorship. This creates a vicious cycle whereby the more proactive efforts to remedy misinformation is labelled as censorship, the less the site will be incentivized to remove that content next time. Companies investing in this space need to balance effectiveness of their algorithms with labelling explainability.

Further, I believe it is important for these solutions to be built at the network infrastructure and/or corporate level rather than by targeting consumers and helping them discern misinformation from authentic and valid content at a micro-level. For example, Logically, is a company that provides browser extensions and augments content to help content consumers identify fake news themselves. Social media and the rapid fire volume of content on the internet have caused deep seated psychological changes to the average human attention span. As digital attention spans decrease, I don’t think a sufficient solution to disinformation can be to fight that trend solely by relying on consumers to use up extra time and mental energy to analyze the sources of each claim in each piece they are reading. I do think this is a nice tool for those who are motivated to fact check their own claims, but that there needs to be investment in filtering out, authenticating and tagging content at a higher level than the consumer: at the source-code, infrastructure or network level.

Private Sector Incentives

I think most people who care about the future of our country (even of the world) would agree that creating technology to combat misinformation is morally good for society. The issue is how to tackle such a large social problem in a commercially viable way. I believe legal regulation is a necessary long-term catalyst to enabling these businesses to flourish. Absent government regulation to more punitively crack down on and address misinformation in big technology and big media (especially social media aggregators like Facebook, Twitter, Snap, etc.), corporate America will lack the incentives to change their ways on their own. I do believe regulatory change will come over the long-term. However, entrepreneurs cannot build business on that uncertainty. Besides companies that sell directly to governments, like Sentinel, I believe there are two business models that are currently and simultaneously commercially viable and also could create the building blocks to address broader misinformation after a regulatory catalyst event.

Trojan Corporate Use Case - the type of technology infrastructure that would be effective at detecting and eliminating misinformation could be targeted first in a corporate setting. Fake news is costing the global economy $78 billion each year. Companies lose potential business and revenue opportunities due to fake news and false claims about their own products, services and brands. This is just one corporate use case where there is misinformation that causes a measurable loss in value to corporations. Companies should be willing to pay for software to address brand misinformation and these dollars can be used to build out a broader set of tools with the power to aid in targeting broader misinformation further into the future. These are the types of use cases that entrepreneurs can focus on in the short-term, even if just a trojan use case for their long term mission and vision of addressing the full fake news / misinformation ecosystem. If the technology that addresses this corporate use case is built to be scalable to other parts of the information ecosystem, these types of businesses would likely own numerous additional monetization paths as governments begin more heavily regulating false information claims over the longer term to catalyze compliance-driven demand in other areas.

Diamond Media / Information Brand - Another potential path is to build out a media, information or data business that both i) strives to differentiate its brand through accuracy of its information and ii) maintains that brand with a specific set of tools / infrastructure that could later be sold to other media, software and / or information businesses. The NYTimes is a great example of a news brand that has established a reputation in the market for truth seeking. While they are investing in content authenticity initiatives like Project Origin, their proprietary tools and processes related to their own fact checking may not be as marketable or applicable to other industries as media sites that simply curate content from other sources. One startup that stood out to me as creating this brand in a scalable way is Golden, a wikipedia alternative focused on emerging technologies. I caught up with Golden founder Jude Gomila to explore how he has built Golden in a way that helps prevent the spread of misinformation and how the business has been forward thinking in preserving the truth in its content through scale. Please enjoy this snapshot of my conversation with Jude.

A Snapshot of my Conversation with Jude Gomila (CEO of Golden)

JG: Accuracy of information is very important at Golden and there is a lot we do to ensure we are not spreading misinformation.

First, transparency is very important. We force individuals coming in to make changes to our pages to use their real identities. For a series of changes made, we also track a full audit log so that changes are publicly auditable and traceable to the author of each word. Making this history of changes much more visible is important to ensuring accuracy. On Wikipedia, it is very tough to track a comparable audit log. Great UI can make this easier for the average user to track.

Second, incentives need to be aligned for information-based businesses. We live and die by our data quality because we are a subscription payment model. Our company is structured so that we have a market mechanism incentive to further improve data.

Third, AI can help improve data quality and combat misinformation. If a VC firm on one of our pages were to change their AUM units from billions trillions, we can use anomaly detection to parse through natural language and call out these fringe cases that are most likely not true.

Fourth, we allow for more granular and higher resolution citations. On Wikipedia, there are limitations to the subsets of words you can tag for a specific citation. Golden lets you create very specific boundaries for citations so there is no confusion as to what part of the paragraph the source applies to. As we scale, we will be able to leverage AI to create an auto-citer that tags data in a traceable, efficient and accurate manner.

Lastly, because we have content and research across many topics, we can use cross-correlation of structured data that we have already tagged to validate whether a new claim is probably accurate or inaccurate.

There are numerous other ways we ensure data quality, but these are just a couple that come to mind. Golden could be a nice infrastructure for knowledge and is getting better and better over time. I care about combatting misinformation personally. Golden could be a nice backbone for knowledge on the internet, but it is useful to have a combined AI and human approach. The more sources of information a platform looks at, the better, to build a more accurate picture of the world. With the amount of misinformation out there, we are already living in an era of probabilistic truths and the source that can represent that best needs to look at the most sources of information.

I also had the chance to ask Jude about how he sees his user base evolving over time:

JG: The current client base consists of government and corporate clients. Every company is becoming a tech company especially due to COVID-19 forcing remote work and leverage. All companies need to get smarter on technology, including niche technologies that would not be covered on Wikipedia because it is below their notability threshold. There are non-paying customers as well who benefit from our curation of knowledge. Ultimately, when you open up your browser and want to know something there should be one place that you look. Golden wants to eventually be that compiled version of truth. This does not mean a single source of truth but rather a compilation of truth across nodes in the network, parsing through sources across the web to present the most accurate aggregation of digital truth. Uncovering those different parts of the network are important to reflecting the truth accurately.

Knowledge APIs and Government Foresight

Golden is building an information business first centered around technology that is differentiated by its claim sourcing, authentication and vetting infrastructure. Among other things, Wikipedia was supposed to be a centralized repository for truth online but has not lived up to that expectation. I believe there is an opportunity for an information or media company like Golden to eventually expand beyond their domain expertise (emerging technology in the case of Golden) and build out a repository for broader information and truth similar to Wikipedia. Even Golden’s initial use case is quite wide as other industries continue to converge with the technology sector. This Wikipedia 2.0 can be done with scaleable 21st century AI and data-rich aggregation methods that parse the web to create a more comprehensive and truth seeking aggregation / mapping of human knowledge online. Eventually, I believe a better constructed knowledge engine, a Wikipedia 2.0, could effectively be leveraged as a set of “knowledge APIs” that developers can build into new media sites and applications that call to the knowledge API to validate a claim as true or improbable before being served to an end user. These APIs could build on the provenance model by going beyond media provenance to media procreation: that is moving from identifying and tracking the source of true content to actively involving truth-seeking and fact-checking in the content and information generation process to begin with.

Further, I found it interesting that many of Golden’s initial clients are in the government sector especially given Golden’s focus on emerging technologies. This is exactly the type of investment governments need to be making to stay ahead of the curve and preemptively regulate up and coming technology businesses instead of constantly playing defense. Much of the “low notability” technology trends that Jude mentioned go unnoticed by government until they are too large to effectively regulate. All emerging innovations have unintended negative consequences, some worse than others: the impact of blue light from computers, greater risk for cancer from sugar substitutes like sucralose, cyber bullying and fake news from social media companies to name a few. The nature of innovation is that it pushes past the frontier of existing human knowledge and society needs guardians who consider the dark side of innovation as that frontier expands. In addition to governments working collaboratively to address the current misinformation crisis, they also need to be tracking up and coming technologies and working hand in hand with entrepreneurs to ensure the next generation of technology companies are building with a more socially conscious growth mindset. I am not saying that the negative impacts that certain technologies have on society are intentional in anyway. In fact, they are almost always unforeseen. Entrepreneurs are the least likely to see the dark side of their innovation early because they are so focused on their mission and the good they think it will bring to the world, that they are less likely to invest time and resources considering what is socially wrong about the venture they are pouring their life and money into. Going forward, government and investors need to play a more active role in identifying the dark side of innovations and setting regulations and allocating capital respectively to balance economic productivity gains with socially desirable outcomes.

Governments should also appoint more individuals with technological backgrounds so they can better discern which technologies need to be regulated more and which present the best opportunity to positively impact the shape of an emerging industry. For example, if we were to rebuild the internet today from the ground up, there are numerous changes that I would think governments would want to incent relevant corporations to pursue through regulation including building in a trust layer, identity verification and lesser reliance on advertising models. However, now that the internet information ecosystem is so highly developed and complex, it is much tougher to regulate.

Governments need to identify major shifts in technological modes that create the best opportunity to positively regulate a new enabling technology. Going forward, as quantum computing and its associated networks are built up, this could be a good target or perhaps more sophisticated forms of AI. Too much of the US government’s interactions with the startup ecosystem are concentrated in identifying better defense technology: for example, through the CIA’s venture capital arm In-Q-Tel. The government needs to conceptualize startup technology not only as an incubator for improved national security but also as a consistent but unintended weapon of industry. Some of these technologies themselves can pose a threat to social stability through perverse consequences of innovation and regulators must work collaboratively with entrepreneurs at earlier stages to ensure business models are sufficiently aligned with the public good.

All Innovation Armory publications and the views and opinions expressed at, or through, this site belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, employers, institutions or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity. All liability with respect to the actions taken or not taken based on the contents of this site are hereby expressly disclaimed. These publications are the blog owners’ personal opinions and are not meant to be relied upon as a basis for investment decisions.